JSDoc, a Stairway to TypeScript

Table of Contents

In this post, I will be using the contents of this repository: https://github.com/Imballinst/jsdoc-sample.

I have been using TypeScript for almost 1 year and I’ve got to say, I really enjoy working with it every day. I feel someone — or rather, something — is watching me writing my code. If I have an error, it will scream next to my ear and it won’t stop until I fix it. This is a blessing, well, most of the time anyways. There were times when I wanted to bang my head to the wall because there were cryptic errors that I couldn’t quite solve easily.

While that’s happening, I also have been reading other developers’ thoughts on TypeScript. Some are afraid to try it because it is intimidating, while some other really love it. Well, people have their own opinions. For me, why do I love TypeScript? It guides me.

Imagine walking on a road. In a normal, sunny day, you will be able to see the road track, which keeps you on the road and prevents you from getting lost. Now, let’s say there is a blizzard. Then, the road track is buried deep beneath the snow. It is now harder to find the way to your destination. You can brute force your way by going in all possible directions, but how long will it take?

When you can see the road track, you don’t really have to think. You just follow that track and eventually it will get you somewhere. If you are lost, then you can go back, using the same road track to your previous checkpoint.

This is similar with a codebase. A simple function is easy to understand, its track is clear. However, in a more complex function, the code flow can be harder to follow, let alone if the variable names do not quite represent what they actually contain. For example, there is a variable named `books`. What is it? An array of `string`, or an array of `Book` objects? We don’t know that information in plain JavaScript — unless the writer puts a comment on it.

Okay, nice — so we can put a comment to “explain” a variable. However, how many lines of comments that you need to write if there are a lot of complex variables? The benefit that your team gets is really small compared to the effort that you do. TypeScript can be the answer here, but let’s assume that TypeScript is intimidating and we want to start slowly. Where do we start?

Introducing JSDoc

You might have heard about JSDoc. It is a tool to document your codebase by utilizing the JavaScript comments syntax. In JavaScript, there are 2 ways to write a comment.

// This is an inline comment.const x = 1;

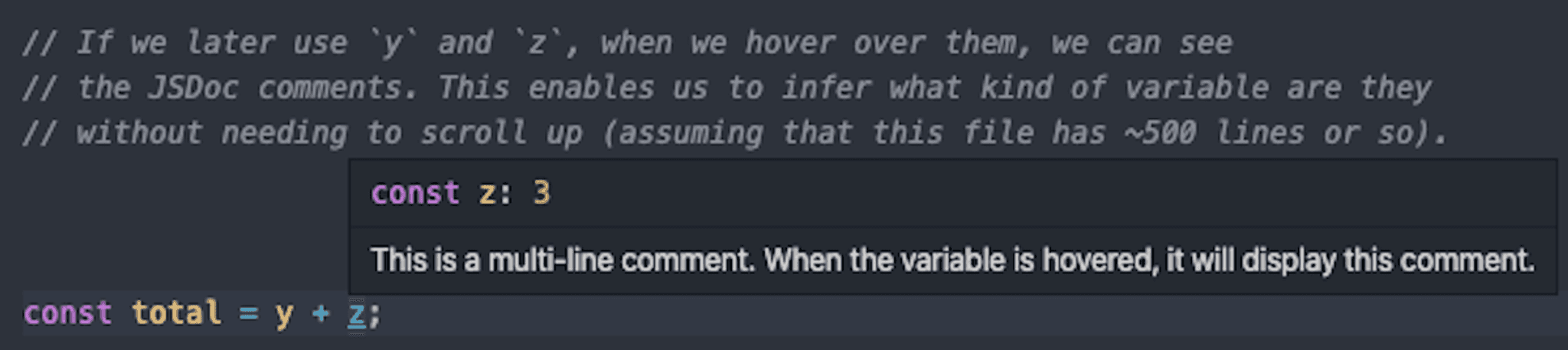

/** This is a multi-line comment. When the variable is hovered, it will display this comment. */const y = 2;

/** * This is a multi-line comment. * When the variable is hovered, it will display this comment. */const z = 3;

// Note that the output comment for `y` and `z` are the same, despite we use line break in the comment.For comments that are following the `/** content */` syntax, in modern IDEs, such as Visual Studio Code, they will automatically infer it as JSDoc documentation comments. This enables developers to quickly look up about the definition of a variable without changing context (e.g. open another file, scroll up/down, etc.). For example, if we hover on variable `z` in Visual Studio code, it will show a tooltip as the following:

Now that we have covered the basic comment feature of JSDoc, what other things that we can do with it?

Function Parameter

With JSDoc, we can add more details to a function. For example, consider this function to get a sum of 2 values:

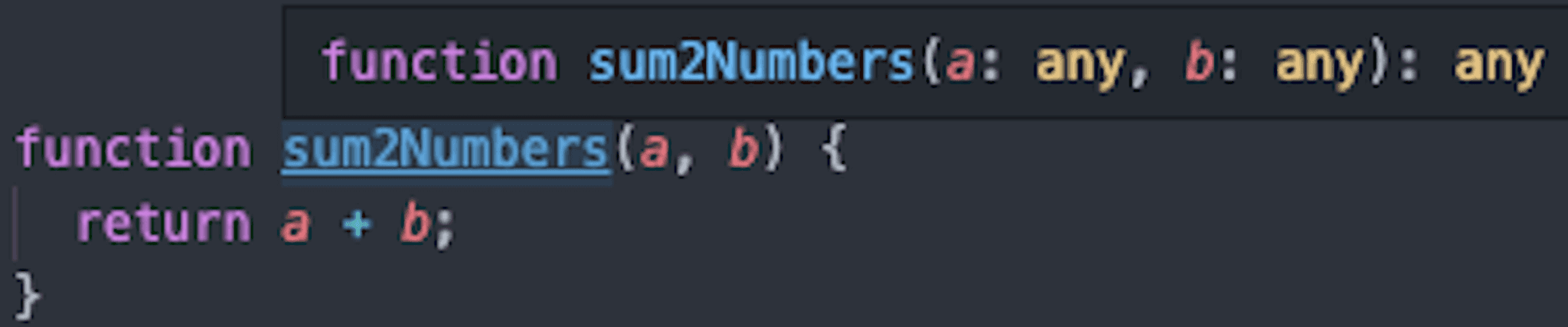

function sum2Numbers(a, b) { return a + b;}When we hover over the function in Visual Studio Code, it shows a tooltip like this:

Do you notice something strange? Yes. The 2 parameters are described as `any`, which can be any type of variable. This is not what we expect, because the function is intended to only sum numbers, not other types. Don’t worry, JSDoc has it covered for you with the function parameter feature.

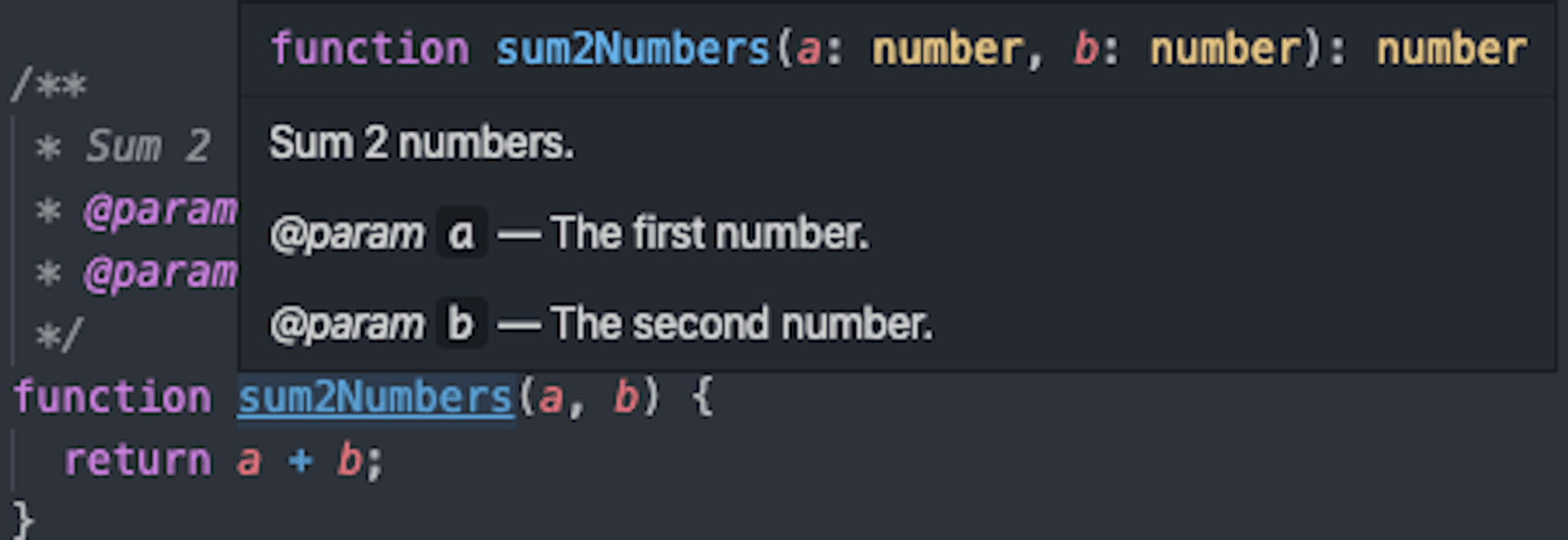

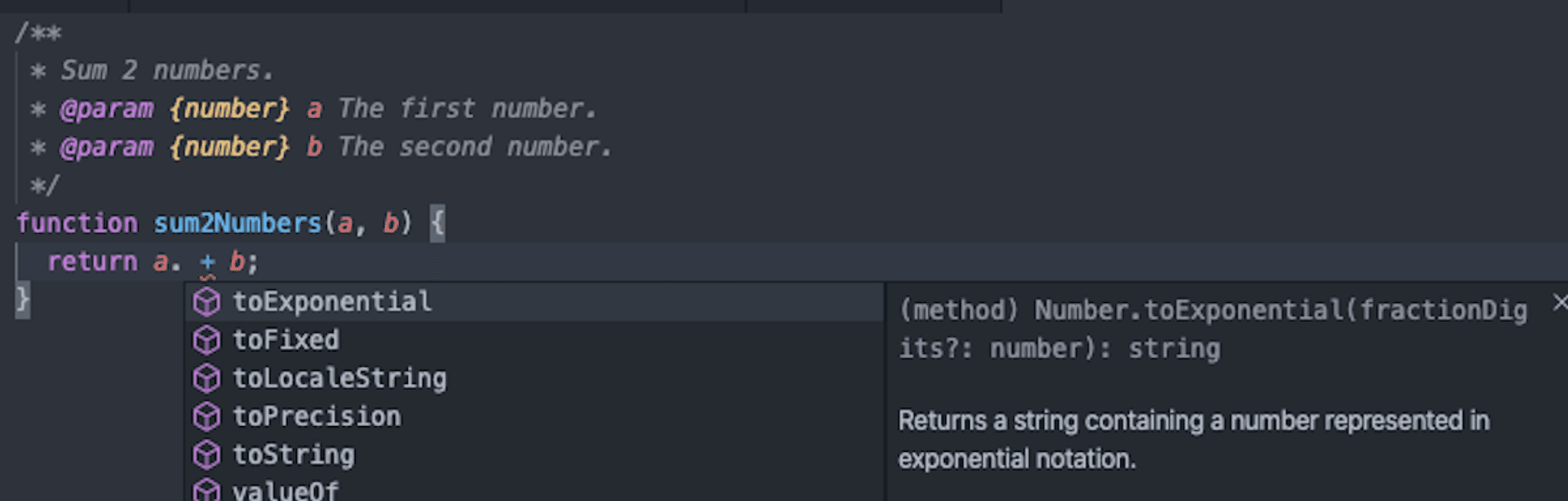

/** * Sum 2 numbers. * @param {number} a The first number. * @param {number} b The second number. */function sum2Numbers(a, b) { return a + b;}Now, with these 5 additional lines, what will happen if we hover on that function once more?

Wow! The `any` types have been changed to `number`! This is amazing, because we have reduced the possibility of our team from misunderstanding this feature. You can also do the same with other primitive types, such as `string`, `Object`, and `Function`. For array types, you can use `Array<type>` or `type[]`, e.g. `Array<number>` or `number[]`.

On top of that, since most modern IDEs are really smart to infer the type from the JSDoc comments, we can capitalize on the suggestions feature. For example, if the IDE knows that both parameters are of type `number`, then it will show suggestions containing all properties and instance methods of the Number object, as shown in screenshot below.

Type Definitions

We have covered the primitive types, but what if we have a quite complex object? Say, we have a “database” which consists of list of authors and list of books:

const db = { authors: [], books: []};

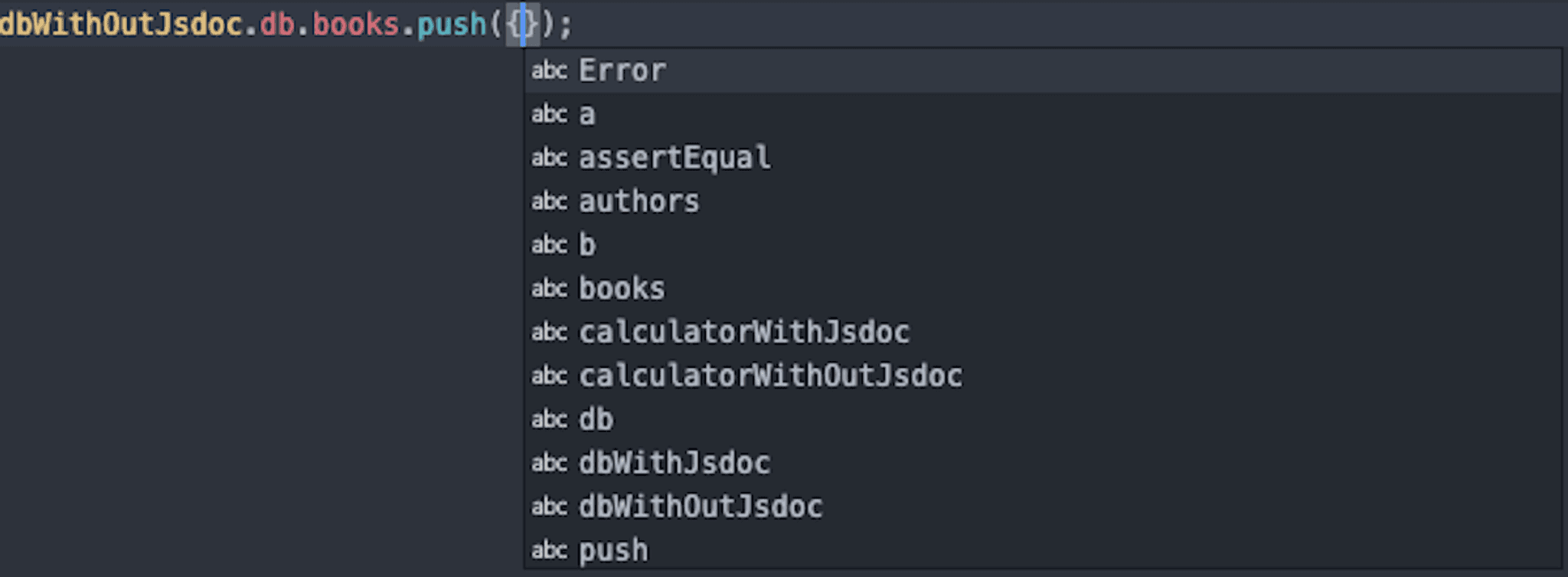

module.exports = { db };This `db` variable contains 2 keys, `authors` and `books`, both having an array as their values. Do we know what kind of value should we insert to these 2 arrays? No. We can test it by trying to add an element to `db.books`:

As shown in the screenshot above, the suggestions do not help us in any way. What we want to achieve is “typed” arrays for both `db.authors` and `db.books`. In order to express that in JSDoc, here’s what we can do:

/** * @typedef Author * @type {Object} * @property {string} id * @property {string} name * @property {string} [address] */

/** * @typedef Book * @type {Object} * @property {string} id * @property {string} name * @property {string} [release_date] */

const db = { /** @type Author[] */ authors: [], /** @type Book[] */ books: []};

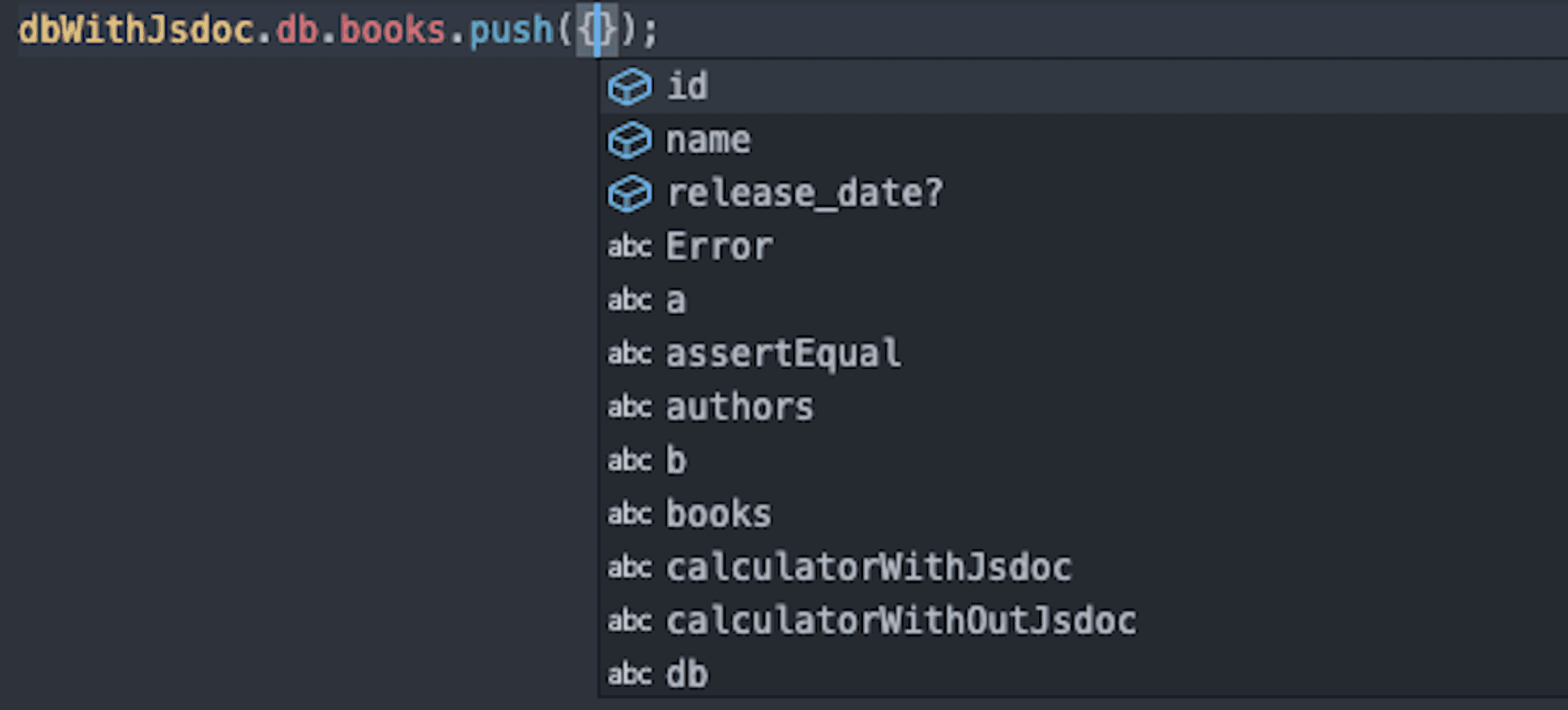

module.exports = { db };Here, we have defined 2 types, `Author` and `Book`. You may have noticed the brackets on the field `Author.address` and `Book.release_date`. This is used to indicate that the bracketed field is an optional field (can be left `undefined`). Let’s take another look on the Visual Studio suggestions:

Cool! Now, we don’t need to remember which fields are required and which fields are optional, because our IDE guides us. Remember when I mentioned about “road track” above? This is the IDE’s “road track”, which we use to delegate the burden of recalling required and optional fields of a certain typed object.

Comparison with TypeScript

So, how good is JSDoc? I’d say it’s pretty good. However, for comparison purposes, let’s replicate the example repository in TypeScript, shall we? Inside the repository, there is a file `with-ts/all.ts` containing the TypeScript equivalent. Alternatively, you can also open this TypeScript playground link.

For the file `db.js`, there is not much difference. We just translated the JSDoc syntaxes to TypeScript types:

type Author = { id: string; name: string; address?: string;};

type Book = { id: string; name: string; release_date?: string;};

const db = { authors: [] as Author[], books: [] as Book[]};However, for `calculator.js`, it’s a bit tricky, because function overloading and TypeScript aren’t exactly the best friends.

function sum2Numbers(a: number, b: number) { return a + b;}

function sum(...numbers: number[]) { let total = 0; let array: number[] = [];

if (arguments.length === 0) { throw new Error('Arguments length should be more than 1.'); } else if (arguments.length === 1 && Array.isArray(arguments[0])) { array = numbers; } else { array = arguments as any; }

for (let i = 0, length = array.length; i < length; i++) { total += array[i]; }

return total;}

interface SumOverload { sum: { (a: number, b: number): number; (numbers: number[]): number; (...numbers: number[]): number; };}

const sumOverload: SumOverload = { sum(numbers: any): any { let total = 0; let array: number[] = [];

if (arguments.length === 0) { throw new Error('Arguments length should be more than 1.'); } else if (arguments.length === 1 && Array.isArray(arguments[0])) { array = numbers; } else { array = arguments as any; }

for (let i = 0, length = array.length; i < length; i++) { total += array[i]; }

return total; }};For the `sum` function, we need to cast `arguments` to `any` because `number[]` can’t be converted to type `IArguments`. On the other hand, in `sumOverload`, we can give 3 kinds of input parameter to `sumOverload.sum` function: (1) 2 number parameters, (2) an array of numbers, or (3) more than 2 number parameters. As written in “Functions Overloads” section of TypeScript documentation, although we only need to implement the function once, we will need to express all possible overloads in the `interface`.

Lastly, the `test.js` is just the same, except the function definition for `assertEqual`.

function assertEqual(a: any, b: any) { if (a != b) { throw new Error(`${a} not equal ${b}`); }

return true;}

// Test calculator functions.assertEqual(sum2Numbers(1, 2), sum2Numbers(1, 2));assertEqual(sum(1, 2, 3), sum(1, 2, 3));assertEqual(sumOverload.sum(1, 2, 3), sumOverload.sum(1, 2, 3));assertEqual(sumOverload.sum([1, 2, 3]), sumOverload.sum([1, 2, 3]));

db.books.push({ id: '1', name: 'Some random book'});db.authors.push({ id: '1', name: 'John'});TypeScript has the same suggestions feature like JSDoc, but more powerful. If you push an object with invalid/missing properties to `db.books`, the IDE will show an error. This is really useful because that kind of error usually won’t show themselves until we run the code.

So, what do you think? I think JSDoc really bridges the gap between “plain JavaScript” and TypeScript. With that said, I prefer TypeScript than JSDoc, because not only the former is more expressive than the latter, but also because TypeScript is far richer in terms of features than JSDoc — one of them is the compile-time type checks instead of runtime. For me, this is a deal breaker as I can prevent errors before they happen.

Conclusion

Well, that’s it! We have covered the key features of JSDoc. By combining JSDoc and modern IDEs, we can utilize the suggestions feature of our IDE, which lifts the burden of recalling small things. JSDoc and TypeScript share a lot of things in common — from describing data structures to autocomplete/suggestions. However, even with JSDoc, it’s quite hard to analyze `TypeError`s in the code before runtime. As such, we can’t quite go autopilot when writing the code.

This is where TypeScript goes in. Now that you have become familiar with JSDoc and its syntaxes, I think you will have a better time writing TypeScript stuff, because you don’t have to use multi-line comments to describe something. Moreover, you will be protected from runtime `TypeError`s, because they all will be caught during the compile time. Now, say it with me: “Bye-bye, runtime TypeError!”.

…wait. Unless you are using `any` in a lot of places, that is.

So, yeah. Hopefully this post is useful to you. Good luck!